Introduction

Hi, I am Mr Young-Gil Kim. Through this Crowdfunding platform, I would like to introduce myself to you and explain my PhD fieldwork project. By reading this post, you could understand why my PhD project is important and therefore I hope you are happy to join this Crowdfunding.

Hi, I am Mr Young-Gil Kim. Through this Crowdfunding platform, I would like to introduce myself to you and explain my PhD fieldwork project. By reading this post, you could understand why my PhD project is important and therefore I hope you are happy to join this Crowdfunding.

I would deeply appreciate it if you could read this post with patience.

Who am I, and What is my story?

It is my honour to introduce myself to you. I was born in South Korea. After obtaining my Master’s degree in International Relations from Korea University in 2007 and teaching cadets at Korea Army Academy International Relations from 2007 to 2009 as a military officer (lieutenant / lecturer), I wanted to contribute to making the world more peaceful and prosperous, so I served as a foreign aid worker of the South Korean government aid agency for around an 8 year period: I worked as an expatriate in Timor-Leste for over a year; I travelled to 14 countries such as Afghanistan, Cambodia, China, El-Salvador, Timor-Leste, India, Mongolia, Morocco, Pakistan, the Philippines, Senegal, Thailand, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam; and I worked with diverse entities such as UN agencies, international NGOs, and government officials of the developing world.

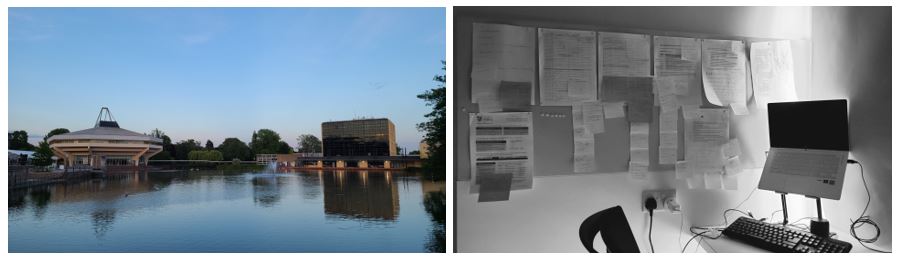

Picture I: My Journey before settling down in Academia

At the end of the long journey, I was eager to know whether the world is de facto getting to become more peaceful, prosperous as a result of the UN’s and the Western donor’s efforts; thus, I quit my job and became a PhD Researcher in the University of York in 2020. I am now a year 3 PhD student of Global Development at the Department of Politics as well as Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre.

Picture II: The University of York, and My Desk

A ‘Short’ Summary of My PhD Project

*This is a short summary version of my PhD project. For the detailed version, please refer to the last section of this post.

This starts from the UN’s liberal peace mission. During a post-conflict era, the UN conducts a peace mission, which introduces four main tenets (human rights, the rule of law, a market-oriented economy, and democracy) in a war-torn society by establishing and strengthening formal institutions. Here, formal institutions can be briefly defined as the state/government organisations.

However, the result of this liberal peace is often at odds with what it promises to deliver. Recent empirical studies suggest that informal institutions – those who govern people’s behaviour outside the state/government organisations – and their relationships with formal institutions are currently thought to play a more important role in governing many aspects of people’s everyday lives. In keeping with this, I would like to explore how the problem of competing claims to land is addressed in Timor-Leste today, a post-conflict era, with a focus on formal-informal institutional relationships.

With literature review, and based on my diverse experiences travelling to 14 countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Senegal and so on as a foreign aid worker, I know that land disputes often accompany conflicts. Also, according to several Timorese elites I met during my scoping trip to Timor-Leste between 10 Oct and 14 Oct 2022, the competing claims to land in Timor-Leste have just started erupting. Furthermore, I do not want to ignore a USAID’s security analysis report arguing that one of the reasons why the conflict between Timorese police and Timorese army in 2006 turned into a nationwide crisis was the ‘unsolved’ problem of competing claims to land. Leaving the land problem unsolved or addressing it without a proper strategy would therefore make the Timorese bright future entangled with another crisis. Consequently, I would like to argue that addressing the problem of competing claims to land in Timor-Leste is a critical issue now.

The brief background is as follows. First, during the Portuguese colonial rule (17th century to 1975) its regime approved land rights, however during the Indonesia occupation period (1975 to 1999), the Indonesia regime approved its own land rights at its convenience, simply ignoring what the Portuguese approved. Second, the concept of customary land rights has been influential in rural areas even during the two regimes. Third, during the Indonesia occupation period, many Timorese had to be internally or externally displaced due to serious human rights abuses by Indonesia regime. It was so brutal that the UN approved the Australia-led multinational peacekeeping army (International Force East Timor: INTERFET). When INTERFET intervened in 1999, the Indonesia army was forced to retreat, and the peacebuilding by UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) began. As a result, a post-conflict era finally began in Timor-Leste; some Timorese tried to come back to their hometown. However, it was not an easy task because many of the new settlers, who are also displaced Timorese, did not want to move again. It is therefore not surprising that the ‘complex’ land problem was not properly addressed by UNTAET between 1999 and 2002, and beyond. As of today, it is common that there are currently multi-layered land rights in one place or ‘competing claims’.

What kind of solutions to the land problem exist in Timor-Leste today? Based on the recent empirical studies on formal-informal institutional relationships, I managed to find that there are two types of institutional solutions to the land problem in Timor-Leste as of today: formal institutional solutions (for example, people come to the government land agency) and informal ones (for example, customary leaders arbitrate in the land problem). Both of them co-exist in Timor-Leste; their relationships can be theoretically complementary, competing, substitutive, or so on. Then, which type of formal-informal institutional relationships would lead to better processes and outcomes of the land problem solving in Timor-Leste today?

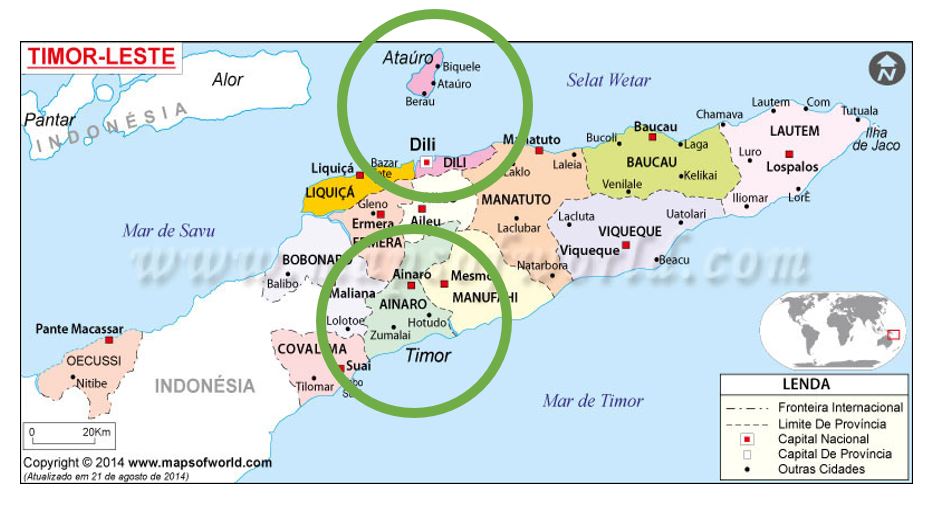

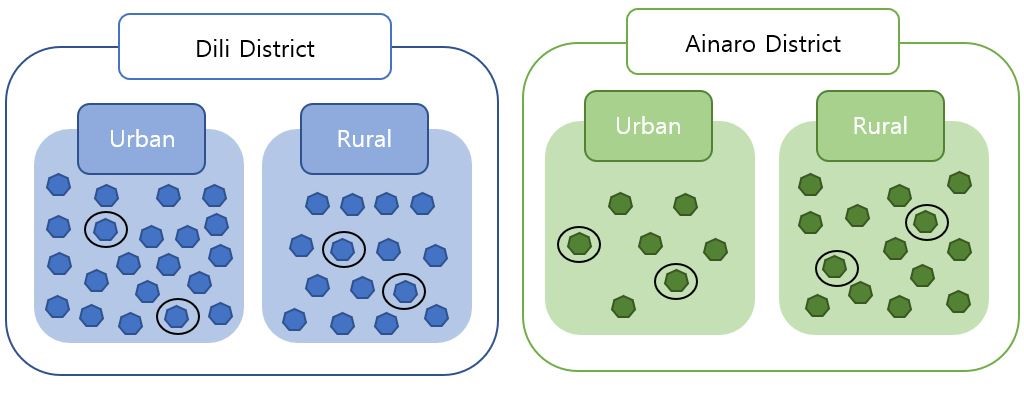

In order to answer this, I will go to Timor-Leste. I will compare Dili district where formal institution building was mainly focused on by the UN and so the presence of formal institutions is strong and Ainaro district where the UN’s outreach was limited and so other informal institutions such as customary institutions play a complementary or substitutive role. Within each district, I will also compare rural areas where people can hardly find formal institutions whilst they find informal institutions more easily and urban areas where people can have easily access to formal institutions. By conducting this fieldwork, I will describe and categorise different types of formal-informal institutional relationship, and analyse their effects on the processes and outcomes of the problem solving.

Thus, instead of wishing that one day formal institutions established and strengthened by the UN can be as effective in their operations as those in the developed world, I hope to find better formal-informal institutional relationship types, which could lead to practically better processes and better outcomes of the problem solving during the post-conflict era in Timor-Leste.

Where will the money go?

My fieldwork is comprised of four sub-fieldworks: one is to be conducted in Ainaro district (urban and rural areas) between January and March 2023 (3 months), and another is to be conducted in Dili district (urban and rural areas) between April and June 2023 (3 months).

My fieldwork accommodation budget is insufficient. I assume that I will at least need £2100 (£200 x 3 months in Ainaro and £500 x 3 months in Dili) for the accommodation fee. This Crowdfunding will be allocated to this budget item. If the Crowdfunding exceeds the funding target, the rest of them will be used for other academic purposes such as buying more books, paying some of my tuition fees, and so on.

What can be offered to you? your reward?

First, the most important reward for you is ‘intangible’. Your donation will ensure that I will be wholeheartedly able to devote myself to the peacebuilding study without financial problems. By doing so, I will be able to produce better academic and practical performance ‘due to your generous donation’.

Second, your ‘tangible’ reward is also important. The types of rewards depend on how much you help me as follows:

(1) If you donate £30, I will send you a thank you card; this card is made in Timor-Leste.

(2) If you donate £60, I will send you the card and Timorese coffee (small size).

(3) If you donate £90, I will send you the card and the coffee (medium size).

(4) If you donate between £100 and £499, I will send you the card and the coffee (big size).

(5) If you donate between £500 and £1000, I will send you the card, the coffee (big size), and my PhD thesis book (a printed version).

(6) Regardless of how much you help me, if you wish, your names will be recorded in the acknowledgement section of my PhD thesis book, and your comments on the world peace – it does not necessarily have to do with Timor-Leste; you could say anything (your hope, your prayer, your opinion and so on) – will also be written there. Your voices will be heard! The world peace can be made together. The more we gather, the more peaceful the world will be!

Find Me Here

I plan to disseminate my research findings by making a presentation in front of diverse people from the UN, international NGOs, donor agencies, Timorese government, and so on in Timor-Leste. I will record my presentation, and upload this in my personal YouTube channel.

On top of that, I will record my PhD journey including how I conduct my fieldwork in Timor-Leste, which books or academic papers in Politics / International Development / Peacebuilding areas are worthwhile to read, how I cope with the arduous PhD process in the UK, and so on. These will be uploaded in my YouTube channel.

Furthermore, you could also find me playing the guitar and singing a contemporary Christian song. I sometimes play the piano as well. I hope you enjoy and appreciate my performance there.

My YouTube channel address is

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UChZCxseAwozyVogL0s5PlEQ

A Good person is who I am

I could say that I am a good person. You could believe that I, as a PhD researcher, will remain good as I have been good in other areas of my life so far.

Picture IV: I used to serve as a COVID-19 response team member in South Korea.

Picture V: I used to serve the old via church: serving food, visiting their home and fixing utilities such as a fan, and entertaining them in church.

Picture VI: Last, but not least, I am a good uncle.

A ‘long’ summary of my PhD project

*Some of my audiences I already contacted were interested in my research in detail. I therefore prepared a ‘long’ summary version of my PhD project aside from the short summary version I mentioned above. If you are extensively interested in what I am going to explore in Timor-Leste, I would like you to read the following article.

My research – my PhD thesis title is ‘Formal-Informal Institutional Relationships and Diverse Ways of Problem Solving in a Post-Conflict Context: A Case Study of Land Disputes in Timor-Leste’ – starts from the UN’s liberal peacebuilding mission, which introduces four main tenets (human rights, the rule of law, a market-oriented economy, and democracy) in a war-torn society by establishing and strengthening formal institutions briefly defined as the state/government organisations. However, the result of this liberal peace is often at odds with what it promises to deliver. According to recent empirical studies, informal institutions, which can be briefly defined as those outside the state/government, as well as their relationships with formal institutions are currently thought to play a more important role in governing many aspects of people’s everyday lives.

In this context and with my experience of an 8-year foreign aid worker including expat service in Timor-Leste over a year, I, via my PhD thesis, aim to explore how the problem of competing claims to land is addressed in post-conflict Timor-Leste. Just as a footnote, a lifelong friendship between South Korea and Timor-Leste was initially formed when South Korea joined the peacekeeping force (International Force East Timor: INTERFET) in 1999; five Korean PKO soldiers died in the line of duty there.

I would like to argue that addressing the problem of competing claims to land in Timor-Leste is a critical issue now. When I met several Timorese people during my scoping trip to Timor-Leste between 10 Oct and 14 Oct 2022, they said that the problem has just started ‘erupting’. Some said that ‘if people are consistently afraid of the land problem, there will be no one who sincerely dream of developing their own land such as home, building, farmland such as coffee farmland (Timorese coffee bean is great and so a vast area of Timorese land is used for it), community, and country. If people are likely to be evicted without proper compensation in the near future, who will dream of such things?’

On top of that, one shall not ignore that the land problem could be a potential flashpoint in Timor-Leste reminiscing a recent Timorese history. Since 2002 when Timor-Leste managed finally to gain its independence and joined the UN as a member state, the international society has praised the Timorese achievement of democratisation and their potential for development. However, in 2006, a crisis happened. Timorese police and army fought each other, and so the international society had to re-engage in Timor-Leste. As regards this 2006 crisis, USAID (the United States Agency for International Development) analyses that a lot of land/buildings were damaged with an arson attack, and most of them were experiencing ongoing disputes of the competing claims to land. If the land problem remains unsolved, it will cause another crisis in the future.

The Timorese land problem has briefly two backgrounds. First, during the Portuguese colonial rule in Timor-Leste (17th century to 1975) there were certain types of land rights approved by the Portuguese regime, however during the Indonesia occupation period there (1975 to 1999), the Indonesia regime approved new types of land rights at its convenience, simply ignoring what the Portuguese approved. Furthermore, mostly in rural areas, the concept of Timorese customary land rights has been influential even during the two regimes. If there are competing claims to land by more than two people who have a different type of land right, then whose right is more legitimate? The Portuguese one? The Indonesian one? The customary one?

Second, during the Indonesia occupation period, many of Timorese had to be internally or externally displaced due to so many, serious cases of human rights abuses which resulted in the fact that the international society felt obliged not to turn their face away. The UN Security Council therefore approved the Australia-led multinational peacekeeping army (International Force East Timor: INTERFET). When INTERFET intervened in 1999, the Indonesia army was forced to retreat, and the peacebuilding by UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) began. As a result, some of the displaced people tried to come back to their hometown, however many parts of the land in their hometown have been over decades occupied with other Timorese who do not want to move again. The natives and the new settlers have their own strong, legitimate stories.

To sum up, it is common in Timor-Leste that there are currently multi-layered land rights in one place or ‘competing claims’ due to its complex history. It is thereby unsurprising that the complex land problem was not properly addressed by UNTAET between 1999 and 2002, and beyond.

What kind of solutions to the land problem exist in Timor-Leste today? I managed to find that there are two types of institutional solutions to the land problem in Timor-Leste as of today: formal institutional solutions (for example, people come to the government land agency) and informal institutional solutions (for example, customary leaders arbitrate in the land problem). The two different types of institutions ‘co-exist’ in Timor-Leste today.

If I follow the logic of liberal peace, then I cannot explain this phenomenon and am likely to argue that only formal institutional solutions are important; thus, I may suggest a policy which may confuse many parts of Timor-Leste today. However, institutionalism covering both formal and informal institutions – Professor Steven Levitsky at Harvard University developed this theory – could give me a more useful theoretical framework to analyse the phenomenon. According to this theory, informal institutions are as important as formal institutions, and formal-informal institutional relationships can be theoretically complementary, competing, substitutive, and accommodating. Then, which type of formal-informal institutional relationships would lead to better processes and outcomes of the land problem solving in Timor-Leste today?

My research question is intended to ‘describe what’ is really happening and ‘explain why’ it is unfolding in certain ways in the developing world in the Timor-Leste context rather than to prescribe what the liberal peace is normatively arguing. For this ‘empirical analysis’, I will visit Timor-Leste with my own hypothesis: ‘Relationship types between formal and informal institutions may affect subsequent processes of addressing a problem of competing claims to land, and thus outcomes will differ accordingly’.

I will compare Dili district where the presence of formal institutions is strong and Ainaro district where that is not strong. Formal institution building has been mainly focused on Dili, the capital of Timor-Leste, by the UN; thus, the institution building is not as effective in other 12 districts including Ainaro district as in Dili due to the UN’s limited human resources and financial support. As a result, institutional settings between Dili and other districts can be presumably different. In addition, within each district, there is a tendency that formal institutions are stronger in more urbanised areas because formal institutions usually exist there, so people have easily access to them. On the other hand, other informal institutions such as customary institutions are stronger in rural areas because access to formal institutions in rural areas is difficult whilst customary institutions play a complementary or substitutive role there. Thus, I will also compare urban and rural areas within each district.

To sum up, there could be a total of 4 types of institutional settings in my research design: urban Dili, rural Dili, urban Ainaro, and rural Ainaro. I will describe and categorise different types of formal-informal institutional relationships, and analyse their effects on the processes and outcomes of the problem solving.

Figure I: My Fieldwork Sampling (Stratified Sampling)

Figure I: My Fieldwork Sampling (Stratified Sampling)

*The Heptagon above means the smallest, official local administration named ‘Suco’

In conclusion, instead of necessarily privileging formal institutions, I hope to find better formal-informal institutional relationships for a context such as Timor-Leste, which could lead to practically better processes and outcomes of the problem solving today.

At the end of the day, I would firstly like to contribute to theory building which could be conducive to making the world peaceful, and I would secondly like to contribute to policy suggestions for addressing the Timorese land problem in ‘peaceful’ and more importantly ‘practical’ ways.

Thank you!